Transcribe Tombstones

Tombstones were meant as lasting memorials but old cemeteries suffer the ravages of time and weather. Many stones are difficult to read and some are already so faint that deciphering them is impossible.

It is imperative to record tombstone inscriptions before they are lost forever to wind, rain and vandalism. The Tombstone Transcription Project encourages people to survey cemeteries and donate survey copies to the USGenWeb Project Archives for posterity.

There is a web page and coordinator for every state. Send recordings to the USGenWeb Tombstone Project manager for the appropriate state. Find state coordinators at http://rootsweb.com/~cemetery/registry.html.

Contact Pamela Reid, National Tombstone Project Coordinator, 4265 Berwick Pl, Lake Ridge VA 22192; 703-878-0407; [email protected]; http://rootsweb.com/~cemetery.

A Lasting Memorial

With remaining funds from their reunion account, the Busse Family Reunion decided to replace the cemetery monument of ancestors Friedrich and Johanna as a lasting tribute to their memory.

The original, made of marble, was badly deteriorated, so this one was made in granite. The new monument looks much like the original in lettering and symbols, but an area they could not read now reads:

To the memory of Friedrich and Johanna Busse who came to America in 1848. Dedicated by their 7,000 descendants in honor of 150 years in America. June 28, 1998.

“We will give thanks to You forever; from generation to generation we will recount Your blessings!” Psalms, 79:13.

Honoring Pioneers

Cemeteries are one of David Carter’s passions. Carter lives 35 miles southeast of Medicine Hat, Alberta, Canada, and about an hour and a half northwest of Havre, Montana. One of his restored cemeteries draws more than 800 people each year for peace and solace. Some are small family groups who come to pay their respects to family graves.

Carter with his friend, Bob Brown, “adopted” 18 abandoned/neglected cemeteries in southeastern Alberta over the past four years. They say they do it “as a way to honor our pioneers, no matter what their ethnic or religious background.”

Carter and Brown cleared cemeteries that had not been cleared for more than 60 years. They visit each site twice a year to mow and rake tall prairie grass. They planted spruce trees at the four interior corners of each site to mark cemetery location and parameters for future generations. People will be able to locate these prairie grave sites by the appearance of four evergreen trees standing sentinel in the midst of prairie wool. From time to time a few individuals help at various sites. And now the Elkwater Hutterite Colony helps maintain four abandoned cemeteries located on their land.

Yet another friend who is a funeral monument workman helps repair tombstones and makes historic markers to identify the original name and years of operation of each cemetery/church site. They use surplus granite bases from World War II German/Austrian POW graves which were once in Hillside Cemetery in Medicine Hat.

Carter says it all began in 1976 when he discovered an abandoned Anglican/Episcopalian church and cemetery at the west end of the Cypress Hills in Alberta. Over the years Carter and others restored the tiny church and maintained its cemetery. They turned the neglected area into an off-the-beaten-track place of peace and beauty.

They provided two picnic tables, a couple of benches, a horseshoe pit, a tiny-tots and old folks baseball diamond and “the only outdoor toilet for 35 miles in all directions — a very useful convenience!”

The isolated cemeteries have an annual reunion work party in early July. “A number of the descendants of graveyard ‘residents’ come and take extra care with graves of their relatives,” Carter reports. About 125 people attend a brief outdoor church service followed by a garage sale to help pay for maintenance and free lunch (including beer!). They’ve been doing the work party/service for almost 24 years and the sale/lunch for eight years. They also have horseshoes, baseball, kite flying and campfires. Carter prints ribbons with the year printed on them and distributes them to everyone.

At one of the reclaimed sites a cemetery “resident’s” adult grandchild, his wife and children have become some of the best workers and have adopted the cemetery. They clear it at least twice a year. Carter says his “hobby/passion” is a great way for a couple of retired guys to get some exercise, to enjoy the outdoors and to say thank you to the past.

More great cemetery stories!

Margaret Kaffka Garrehy, Sacramento, California, and Pat (Crotty) Glugla, Deerbrook, Wisconsin, met when Naomi Engelmann, indexer at the Antigo (WI) Library noticed that both were researching the same family. What are the odds? The outcome of this chance meeting was a reunion, the Stanislaus Glugla Connection — Greatful Dead Tour, at Queen of Peace Catholic Cemetery in Antigo. The day before the reunion each grave marker was given a final check and decorated with flowers. Margaret and husband, Den Garrehy, parked their motorhome next to the cemetery building to mount a 14-page computer-generated descendant list for Stanislaus Glugla (born 1820 in Poland, emigrated to America in 1870).

Antoinette Kyle Ketner Bengtson, Lincoln, Nebraska, left a note in a bottle at the Gibboney Family Square, East End Cemetery in Wytheville, Virginia. Jean Bourne, a cousin from Blacksburg, Virginia, found the note when she visited the gravesites and the Gibboney Family Reunion found another descendant.

Without plans for internment, Carolyn Sigler Schellang’s only sister Billie Linda Sigler Taylor died in 1995. She wanted to bury her sister in the Sigler Cemetery in Shelby County, Tennessee. Land for the cemetery was donated in February 1870 by Littleton Smith Sigler and deeded to Sigler heirs.

Carolyn was dismayed by the overgrown weeds and broken headstones and discovered that few family members even knew about the cemetery. Maintenance had become too much for family members who were trying to take care of it. She has since been finding and notifying family about the cemetery and has resurrected a family reunion at the site. With money donated by “found” kin they’ve been able to build a fence, a new concrete drive and install a wrought iron half moon over the entrance with the Sigler name in it. She credits her cousin, Ray Sigler, and uncle, Joe Sigler, for their hard work and letting kin know their donations were being spent only for cemetery care.

Finally, one of our favorite cemetery reunions is of the descendants of

Finally, one of our favorite cemetery reunions is of the descendants of

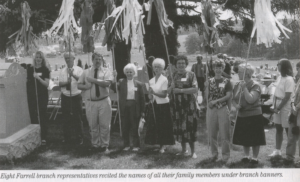

John J. and Mary Jane Farrell held at St. Mary’s Catholic Church and cemetery at Pine Bluff, Wisconsin. Ancestor, James Farrell, hauled the lumber to build the church in the 1850s and five generations of Farrells are buried in the church cemetery. Member and liturgical choreographer, Michele White, Chicago, Illinois, wrote an elaborate performance both in the church during Mass and later in the cemetery. She hand-made banners and streamers of colors representing each of eight siblings from whom reunion members are descended. When Mass ended, someone representing each ancestor led their relatives behind banners to the cemetery. Once there each banner carrier recited the names of everyone in their branch. To the strains of an Irish bagpipe, White danced and connected tombstones with color ribbons to match banners. When it was over and in a soft breeze, the little cemetery was ablaze in a colorful web of ribbons and banners (the video tape is spectacular!!).